Saying “Fuck it” actually motivates me more than “You can do this”.

Because saying “fuck it” includes the total acceptance of failure as the outcome, meanwhile “you can do this” focuses only on the hopes of a successful outcome and the lack of acknowledgement of the equally probable failure outcome induces a certain level of unspoken anxiety

I was presenting an assembly for kids grades 3-8 while on book tour for the third PRINCESS ACADEMY book.

Me: “So many teachers have told me the same thing. They say, ‘When I told my students we were reading a book called PRINCESS ACADEMY, the girls said—’”

I gesture to the kids and wait. They anticipate what I’m expecting, and in unison, the girls scream, “YAY!”

Me: “'And the boys said—”

I gesture and wait. The boys know just what to do. They always do, no matter their age or the state they live in.

In unison, the boys shout, “BOOOOO!”

Me: “And then the teachers tell me that after reading the book, the boys like it as much or sometimes even more than the girls do.”

Audible gasp. They weren’t expecting that.

Me: “So it’s not the story itself boys don’t like, it’s what?”

The kids shout, “The name! The title!”Me: “And why don’t they like the title?”

As usual, kids call out, “Princess!”

But this time, a smallish 3rd grade boy on the first row, who I find out later is named Logan, shouts at me, “Because it’s GIRLY!”

The way Logan said “girly"…so much hatred from someone so small. So much distain. This is my 200-300th assembly, I’ve asked these same questions dozens of times with the same answers, but the way he says “girly” literally makes me take a step back. I am briefly speechless, chilled by his hostility.

Then I pull it together and continue as I usually do.

“Boys, I have to ask you a question. Why are you so afraid of princesses? Did a princess steal your dog? Did a princess kidnap your parents? Does a princess live under your bed and sneak out at night to try to suck your eyeballs out of your skull?”

The kids laugh and shout “No!” and laugh some more. We talk about how girls get to read any book they want but some people try to tell boys that they can only read half the books. I say that this isn’t fair. I can see that they’re thinking about it in their own way.

But little Logan is skeptical. He’s sure he knows why boys won’t read a book about a princess. Because a princess is a girl—a girl to the extreme. And girls are bad. Shameful. A boy should be embarrassed to read a book about a girl. To care about a girl. To empathize with a girl.

Where did Logan learn that? What does believing that do to him? And how will that belief affect all the girls and women he will deal with for the rest of his life?

At the end of my presentation, I read aloud the first few chapters of THE PRINCESS IN BLACK. After, Logan was the only boy who stayed behind while I signed books. He didn’t have a book for me to sign, he had a question, but he didn’t want to ask me in front of others. He waited till everyone but a couple of adults had left. Then, trembling with nervousness, he whispered in my ear, “Do you have a copy of that black princess book?”

He wanted to know what happened next in her story. But he was ashamed to want to know.

Who did this to him? How will this affect how he feels about himself? How will this affect how he treats fellow humans his entire life?

We already know that misogyny is toxic and damaging to women and girls, but often we assume it doesn’t harm boys or mens a lick. We think we’re asking them to go against their best interest in the name of fairness or love. But that hatred, that animosity, that fear in little Logan, that isn’t in his best interest. The oppressor is always damaged by believing and treating others as less than fully human. Always. Nobody wins. Everybody loses.

We humans have a peculiar tendency to assume either/or scenarios despite all logic. Obviously it’s NOT “either men matter OR women do.” It’s NOT “we can give boys books about boys OR books about girls.” It’s NOT “men are important to this industry OR women are.“

It’s not either/or. It’s AND.

We can celebrate boys AND girls. We can read about boys AND girls. We can listen to women AND men. We can honor and respect women AND men. And And And. I know this seems obvious and simplistic, but how often have you assumed that a boy reader would only read a book about boys? I have. Have you preselected books for a boy and only offered him books about boys? I’ve done that in the past. And if not, I’ve caught myself and others kind of apologizing about it. “I think you’ll enjoy this book EVEN THOUGH it’s about a girl!” They hear that even though. They know what we mean. And they absorb it as truth.

I met little Logan at the same assembly where I noticed that all the 7th and 8th graders were girls. Later, a teacher told me that the administration only invited the middle school girls to my assembly. Because I’m a woman. I asked, and when they’d had a male author, all the kids were invited. Again reinforcing the falsehood that what men say is universally important but what women say only applies to girls.

One 8th grade boy was a big fan of one of my books and had wanted to come, so the teacher had gotten special permission for him to attend, but by then he was too embarrassed. Ashamed to want to hear a woman speak. Ashamed to care about the thoughts of a girl.

A few days later, I tweeted about how the school didn’t invite the middle school boys. And to my surprise, twitter responded. Twitter was outraged. I was blown away. I’ve been talking about these issues for over a decade, and to be honest, after a while you feel like no one cares.

But for whatever reason, this time people were ready. I wrote a post explaining what happened, and tens of thousands of people read it. National media outlets interviewed me. People who hadn’t thought about gendered reading before were talking, comparing notes, questioning what had seemed normal. Finally, finally, finally.

And that’s the other thing that stood out to me about Logan—he was so ready to change. Eager for it. So open that he’d started the hour expressing disgust at all things “girly” and ended it by whispering an anxious hope to be a part of that story after all.

The girls are ready. Boy howdy, we’ve been ready for a painful long time. But the boys, they’re ready too. Are you?

I’ve spoken with many groups about gendered reading in the last few years. Here are some things that I hear:

A librarian, introducing me before my presentation: “Girls, you’re in for a real treat. You’re going to love Shannon Hale’s books. Boys, I expect you to behave anyway.”

A book festival committee member: “Last week we met to choose a keynote speaker for next year. I suggested you, but another member said, ‘What about the boys?’ so we chose a male author instead.”

A parent: “My son read your book and he ACTUALLY liked it!”

A teacher: “I never noticed before, but for read aloud I tend to choose books about boys because I assume those are the only books the boys will like.”

A mom: “My son asked me to read him The Princess in Black, and I said, ‘No, that’s for your sister,’ without even thinking about it.”

A bookseller: “I’ve stopped asking people if they’re shopping for a boy or a girl and instead asking them what kind of story the child likes.”

Like the bookseller, when I do signings, I frequently ask each kid, “What kind of books do you like?” I hear what you’d expect: funny books, adventure stories, fantasy, graphic novels. I’ve never, ever, EVER had a kid say, “I only like books about boys.” Adults are the ones with the weird bias. We’re the ones with the hangups, because we were raised to believe thinking that way is normal. And we pass it along to the kids in sometimes overt (“Put that back! That’s a girl book!”) but usually in subtle ways we barely notice ourselves.

But we are ready now. We’re ready to notice and to analyze. We’re ready to be thoughtful. We’re ready for change. The girls are ready, the boys are ready, the non-binary kids are ready. The parents, librarians, booksellers, authors, readers are ready. Time’s up. Let’s make a change.

I had planned to sit down today and give you guys the Handbook For Con Artists recap you crave, but a Twitter conversation prompted me to write this post, which has been coming for a while. I’ve talked on social media (and maybe here) about the fact that my teenaged son is autistic. And I’ve finally got the courage to say that I am, too. I am autistic.

This might have been why I didn’t consider the possibility that my son was autistic until he was seven years old and someone suggested it to me. A lot of the things he did at a young age, like flapping his hands and walking on his toes, melting down when he was overstimulated, becoming passionately engrossed in specific singular interests that could change in an instant, and other behaviors I won’t go into just, you know, because it’s not entirely my stuff to share, were things I had done when I was child, and I wasn’t autistic, so it never occurred to me that he was anything other than neurotypical. Even after diagnosis, I assumed that those were things neurotypical children all had in common and that other things “made” him autistic.

Now, I look back at my own childhood, much of which I don’t remember accurately due to my inability to recall what parts were real and what parts have been obscured by the elaborate fantasies I’d constructed. I was the weird kid in middle school, so I retreated into my head. While I sat at my desk physically, in my mind I was in my “head house,” a space that I constructed after learning about something called the method of loci (not to be confused with the genetics term loci). To this day, when I’m stressed almost to my breaking point, bored to the edge of literal tears, or caught in a situation I don’t want to be in, I fully check out of reality and go there. It’s not a case of idly daydreaming; I am completely immersed in that world and fully absent from this one. It has evolved over time, the decor has changed slightly, and there’s a big giant button on the wall that turns off intrusive thoughts if I push it. It’s a great self-preservation strategy that had a disastrous effect on my education. Teachers asked me why I wasn’t paying attention, why I wasn’t turning in my homework, why I wasn’t completing tests. I couldn’t give them an honest explanation. I told them what they wanted to hear because I already knew I was “a handful,” but lying to them because I thought I was giving the right answer made me even more of a handful, and I couldn’t figure out why.

“Jenny’s a wonderful girl. So imaginative. But she’s a handful.” I’d heard that so many times. Once, back in my elementary school days, I was playing with my cousins after Sunday dinner at my grandmother’s house. Seemingly out of nowhere, one of my uncles became furious at me. I didn’t know why; his kids and I had been playing a game where I was a mad scientist, one of us was an Igor, and one of us was a zombie creature that didn’t have a brain. To this day, I have no clue what I did wrong. Maybe I was too loud and obnoxious. Maybe I hurt one of my cousin’s feelings and didn’t notice, which I was prone to do because I didn’t understand which actions resulted in which reactions. What I do know is that one second we were playing and having fun, and the next my uncle stood up and said, “I’ve had it with that god damn kid!” and stormed out. Everyone sat around stunned. I was humiliated, but I didn’t feel like I deserved to cry, though I wanted to. My mother was furious with my aunt and uncle for weeks. My grandmother fielded hours of mediation phone calls over the incident. That became kind of a hallmark of my otherwise happy childhood: somehow, I would do something wrong, an adult would shout at me in front of people, and I would go off on my own away from the other kids because I saw how much my badness hurt the relationships in my family.

In second grade, I was diagnosed with ADD, like so many kids of my generation, and fed a steady diet of Ritalin. I’m not anti-pharmaceuticals as they’re used today––for god’s sake, take your pills, no matter what indie movies say––but I do believe that Ritalin was over-prescribed in the 1980s as a sort of “make your kid a behave” pill, based on anecdotal evidence from other people my age. Though Ritalin was supposed to make me focus, it did basically nothing. I ended up in some kind of group therapy situation where we all learned coping skills, and that worked better than anything. It was like a guidebook on how to be a normal kid. All I had to do was painstakingly imitate the way other people were acting? I could do that! I loved acting! It didn’t fix everything, but adults stopped yelling and I didn’t get into trouble as much, except where education was involved.

Again, this is stuff I still do. I recently told a friend about one of my most secret desires: to successfully say, “Don’t eat that, it’s horrible,” as a compliment. You know, the way people will tell someone, “Oh, don’t eat any of that, it’s just horrible,” in a joking way that implies they don’t want anyone else to eat it because they want it all? If you’ve never botched the landing on this particular phrase, trust me: there is no coming back from it. I’ve tried it on a few occasions and it did not go over well. I end up replaying it over and over like a gymnast watching themselves on video to see where they made a mistake in their routine. I spend a lot of my time studying neurotypical humans and their interactions as though I’m a complete outsider to the entire species, trying to figure out how to best camouflage myself. It’s just as much work and just as alienating as it sounds. I’m always woefully behind by a decade or so of social development, it seems like. But one day, I fully believe I’ll be able to pull off a chuckle and a “don’t eat any of that, it’s just awful.” I was gently informed that most people don’t practice these types of easy social interactions with the goal of someday doing them correctly.

When my son was diagnosed, I began to seek out other parents of autistic children, because it was something I was told would be very important in helping me “deal” with my child. I didn’t see what I needed to “deal” with; as far as I knew, he was growing up exactly the way I did. I mean, how could I really be sure he was autistic? He was just like me and (all together now), I wasn’t autistic.

One of the things I noticed very early on was that “autism warrior mommies” (and yes, there are people who call themselves that) were easily sorted into three camps. One type became so obsessed with their child’s autism that having an autistic child became their identity and the kid was kind of an afterthought if they were a thought at all. Or, they suddenly started diagnosing their neurotypical children with autism in a sort of Munchausen-by-proxy-by-proxy kind of deal; when the kids would be evaluated and deemed neurotypical, whoever administered the evaluation didn’t know what they were talking about, didn’t listen to parents, shouldn’t be in that profession, had a personal vendetta, etc. Then there was the third kind of parent: the self-diagnosing autism mom.

A note here: Some parents do have to fight to get their kids a diagnosis when resources are denied by schools and government programs. Some parents are autistic and don’t know it until their children are diagnosed, specifically because healthcare providers and educators weren’t as familiar with autism in previous generations as they are now. But as someone who has spent a lifetime carefully studying humans, I feel I can say with confidence that some people are just insistent on being the center of the universe. And that’s pretty evident with some of the self-diagnosing autism warrior mommies. I became highly suspicious of some mothers who would self-diagnose, then start speaking with authority on their children’s’ experiences, even if those children were able to communicate their ideas, feelings, and opinions themselves. They asserted themselves as experts on autism and would become intensely defensive if another autistic person contradicted them or suggested they not share intimate details of their child’s life online. One self-diagnosed woman in a Facebook group graphically described her seventeen-year-old son’s toilet accidents and admitted that he didn’t want her to continue doing it, but she asserted that she was “far more autistic than him,” and therefore had the right to do so. I began to see self-diagnosis as fake and selfish, an attempt by a parent to center themselves when their child was getting too much attention or starting to rebel in the ways children are supposed to rebel.

I wondered why any of these “autism warrior mommies” couldn’t understand that their kids were people. That no tragedy had befallen their families. That they had never been guaranteed a neurotypical child, and that the idea of an autism “cure” was abhorrent when there were already constructive therapies and special education programs that could improve the quality of life for autistic people living in an unforgiving and aggressively neurotypical world. So much of their “activism” was performative and self-pitying. It was never about autistic people at all, but all the ways neurotypical people were burdened by the existence of them. Why couldn’t they see that?

Earlier this year, someone tweeted a link to a diagnostic tool being developed to evaluate adults for autism. I’m not entirely sure about all the specifics about it, but from my understanding, they were looking for both neurotypical people and people on the spectrum to take an online test to…I don’t know. See if their test worked? I’m not a scientist, so I have no idea. I thought, “okay, I’ll bite,” and took the test. When I say “online test,” I’m not talking about some kind of thirteen question, Buzzfeed-esque “design your dream wedding and we’ll guess how autistic you are” quiz. I recognized a lot of the questions from the tests administered to my son and the exhaustive questionnaires my husband and I’d had to fill out during the process. When the results were displayed, it didn’t say “YOU GOT: AUTISM!” with a twee description and a gif from The Gilmore Girls or anything. It just suggested consulting a professional and showed me that my final scores were about a hundred points over the threshold they were using to describe neurotypical people in their diagnostic criteria.

I called my friend Bronwyn Green immediately. “Do I seem autistic to you?” I demanded, and she said yes. I asked why she didn’t tell me: “If I thought you seemed autistic, it would have been the first thing I said to you! I would have been like, ‘hey, you seem autistic!'” She said, “Jen?” and waited silently for me to make the connection. And then the connections kept coming. I showed my husband the scores and he said, “Yeah? You’re autistic.” It was some kind of open secret I had never been in on. And soon, I was a self-diagnosing autism mommy. And I hated it.

Here’s where things really go sideways to me: I believe it when autistic people tell me they’re autistic, even if they’re self-diagnosed. If someone is suffering from anxiety, depression, OCD and they self-diagnose it? It makes perfect sense to me. But it picks away at me to think that maybe I’ve gaslighted myself into becoming self-diagnosing autism mommy. Occasionally, it occurs to me that maybe there’s such a thing as autismdar. Like gaydar, but for autism. I maintain that LGBQA+* identifying people have an innate ability to tell if other people are straight or “one of us” after years of painstakingly pretending to be heterosexual while we’re closeted. Is the same true for autism? Is the reason I resent and doubt the mothers who use their self-diagnosis as both a weapon and a shield because I’ve spent so many years studying neurotypical people as a means of protective camouflage that I can now spot them from a mile away? I’ve met parents who self-diagnosed and thought, “Yeah, sounds about right,” while others I’ve rolled my eyes at and thought, “Yeah, right.” What creates the difference? I can’t diagnose them, so why do I doubt some people but not others?

At this point, you might be rolling your eyes at me and thinking, “Yeah, right.” Because a lot of the times, I’m doing that, too. Despite all the evidence, despite it seeming absolutely natural and right to me to think, “I am autistic,” I worry that those moms who say, “Well, I’m autistic and I support Autism Speaks!” or “I was autistic, until I started focusing on my gut health,” feel like it’s natural and right, too. I’m not the gatekeeper of autism. I don’t know who is. Do I have the right to doubt some self-diagnoses but believe others? Do I even have the right to diagnose myself?

In the middle of all of this soul-searching, two books have been hot topics in the literary world. One of them, written by a woman referred to as the Elmo Mom, details all the ways she’s using “exposure therapy” (i.e., dragging her screaming, terrified child into situations that traumatize him) to right the wrong the universe did when it saddled her with an autistic son. In it, she daydreams about abandoning her son to have a new and better life with her neurotypical daughter. She expresses open hatred and abusive, neglectful behaviors then tries to justify them by imploring the reader to consider her own pain. She relates “and the whole bus clapped”-style anecdotes about kindly strangers coming to her rescue and praising her for her saintliness. She recently wrote an online essay about bystanders cruelly judging her for bodily wrestling her resisting, screaming child into a Sesame Street Live performance, asserting that her son has every right to be there. She never considers that he has every right to not be there, as well. In the end, he does sit through the performance, and she receives her reward: an hour or so of being able to deny that her son has autism.

Another book, the title of which I’ve forgotten, is the memoir of a woman who has no qualms about stating that she plans to have her autistic teen sterilized, lest he impregnate someone and she’s forced to deal with it. You’ll have to forgive me for not looking up this title and author; I just can’t handle reading her sickening garbage, yet I’ll still find myself compelled to.

Several readers of this blog have contacted me about these books, wondering if I would write a post about them or bring attention to them on social media. Like a coward, I ignored those emails. If you were a person who contacted me and didn’t receive a reply, I apologize for my rudeness, but this is all fresh and raw to me. It’s not that I’m struggling with the tragedy of finding out I’m autistic. That part of the experience is very much like the time I found out I have a deformed blood vessel in my brain. It was a thing I didn’t know, then I knew it, but ultimately it hasn’t demonstrated any impact on my life, so it’s just a thing that is. Realizing that I’m autistic was just a moment of, “Oh. Okay, that actually explains a lot of stuff.” It didn’t change who I am as a person or how I view myself. But it very much changes the way I view the people in my life during my childhood.

Now, when I read the disgusting thoughts of the autism warrior mommies who write their memoirs about how sad and tragic their children have made their lives I see myself in the role of that child, rather than as a parent criticizing another parent. I read about Elmo Mom fantasizing about abandoning her child for a better one and wonder if my mother had those same thoughts. Being the consequence of an unintended pregnancy had already put those seeds of doubt in my mind with regards to whether my mom ever regretted having me because of the life she might have had otherwise. It never occurred to me to worry that she might have regretted having me due to me not coming out as advertised. It never once crossed my mind to view my family with suspicion, to think that they might not have been annoyed or disdainful of my behaviors because I was a handful, but because of circumstances that were out of my control. And never in my life have I ever considered that I might have been in danger from the adults who had to care for me. All of this has made me think things about people I love that I don’t want to think. And for that reason, I’ve been unable to write about or think too deeply about these horrible, abusive women who have monetized hating their children.

This post might be super ableist. I can’t tell. It might be unfair of me to opt out of autism activism when other people can’t. That’s a valid criticism. Right now, I’m not even entirely comfortable labeling myself as autistic without some kind of paperwork or certificate to prove it, but I’m unable to separate myself out as an ally, either. I’m interested to hear from those of you who are actually autistic if you’re comfortable sharing your thoughts on self-diagnosis in the comments, whether you’re formally diagnosed or self-diagnosed. It’s a strange experience to be the same person you were yesterday, yet doubt everything about the narrative of your life story today.

*The “T” in LGBTQA+ was removed because I was speaking specifically about sexuality and I don’t know if transgender people have a gaydar equivalent. I excluded the T from the acronym so as not to make assumptions or erase heterosexual transgender people.

The LA Times recently published a piece on the lack of men in OB/GYN. Only 17% of new trainees (residents) in OB/GYN are men and the male OB/GYN physicians who weighed in worried that this “lack of diversity could weaken the field.” Apparently it sends a “horrible message to men” and with the lack of men we might “lose the next person who is going to find a cure for cancer.”

I have some thoughts.

The first one is 55% of pediatric residents in 1990 were women and currently 75% of pediatric residents are women yet I have never once heard any pediatrician talk about how that might prevent us from the next big breakthrough in pediatrics. I’ve never read an article on how the gender discrepancy in pediatrics or family medicine or psychiatry (the latter two also female dominated as approximately 57% of trainees in both are women) impacts those fields either. Then again those fields tend to pay less than OB/GYN.

Is is just acesss to higher paying jobs that is bad for men? Hmmm.

My second thought is I have not read any think pieces on how the dearth of women in the areas of medicine that are still male dominated, such as neurosurgery, affects advances. No one there seems to worry that the lack of woman brain hampers much of anything.

I could just leave it at that, but I’m me and today is International Women’s Day so buckle up.

There are more medical role models top to bottom for men than women

My medical training was 1986-1996. In medical school the only lectures I received from women were given by basic scientists (Ph.D.s not M.D.s) and pathologists. I was never given a lecture by a female surgeon or cardiologist or even a female OB/GYN. Maybe there was one and I was sick that day. I never had one textbook authored or edited by a woman. A chapter written by a woman was a treat.

When I did an elective in the U.K. in 1990 and heard that they referred to surgeons as “Mr.” I asked a male surgeon what that called female surgeons. His answer? There aren’t any.

In my residency there were three female OB/GYNs out of a department of about 20.

During my 10 years of training I never met one female surgeon. Not one. Most of the faculty in all fields were men. I never heard of a female chief of a department never mind meeting one. Not just of OB/GYN, of any department.

What about now? Are there men in leadership positions so male trainees at least have someone to look up to when they take a break from the textbooks largely written by men? The most recent data tells us that for OB/GYN 79.4% of department heads or chairs, 64.9% of vice chairs, and 71.4% of division directors are men. The American Congress of OB/GYN (ACOG) elected its first female President in 1984. In 65 years they have had 5 female Presidents.

The Royal College of OB/GYN in the U.K. has its first ever female President.

Patient Preference

Some women will ask to see a female provider and this bias will be greatest against medical students. This is new. When I trained most providers were men so there was no choice. The few times there were women providers the female patients were less empowered to speak up. Women now have more power to say what they want. That is not a bad thing.

If men in medical school or OB/GYN residencies are working a little harder to overcome some biases then I can assure them from my personal experience that it will make them a kinder, better doctor because they will learn how to gain a patient’s confidence that much quicker. I think every woman of my generation who has been called a “little miss” by a patient and been asked to step aside so the man (a.k.a. real doctor) could do the procedure has some empathy for the situation some men in OB/GYN face today. Although at least men are not sexually decredentialed as they step aside.

It is interesting to hear women who have had bad experiences with doctors talk about their providers. In my experience when they were unhappy and the provider was a woman she was “uncaring” or a “bad doctor.” The men, well, they just “didn’t understand.” That is how systemic our biases are against women.

Sexual Assault and General Demeaning Talk

I’m not sure how many men in OB/GYN have had their scrotum cupped by a female attending in the operating room, but I have certainly been positioned next to a male surgeon so his arm rubbed against my breast for an hour or so. I’ve had more hands run up and down my back and I’ve been corned, literally pushed up into a corner, by a male surgeon trying goad me into letting him drive me home late at night. I’ve also had a tongue stuck down my throat. I know that many men in medicine have been sexually assaulted, but I believe the numbers pale in comparison to the female experience.

Then there were all the times male surgeons and even OB/GYNs spoke about hockey or golf in the operating room in a pointed or “humorous” attempt to exclude me from the conversation. Or the good times when the men in the operating room joked about not knowing how to talk about knitting!

Ha ha.

This not specific to OB/GYN, but just to demostrate some of the additional barriers women experience.

Pregnancy Bias

I have heard story after story of women being turned down or passed over for training positions because they might get pregnant or because they (God forbid) had a pregnancy in residency. A friend of mine wanted to be a neurosurgeon. She applied to a variety of programs in Canada. She was conditionally accepted into what was considered one of the best programs. The condition? She sign a contract stating she would not get pregnant during her residency. This was in 1989. Not 1889, 1989.

I bet not one man in any medical school or residency ever has been asked about his plans for procreation.

Job Bias

If you thought being a woman in OB/GYN brings bigger bucks you would be wrong.

Male doctors who get awards from the National Institute of Health make $13,399 more per year than women doctors (controlled for specialty, academic rank, leadership positions, and number of publications). It’s not about pregnancy or kids either as women with no children still had lower salaries than their male counterparts.

In academic medicine OB/GYN ranks the 4th worst (out of 18 fields) for a gender pay gap. Women in OB/GYN earn $36,390 per year less than men in an adjusted analysis.

Overall (so not just in a university setting) women in OB/GYN make $48,000 less on average than men. This specific data set didn’t control for number of hours worked, however, looking at all the other studies on gender pay gap in medicine that do control for hours worked and other factors it is very likely the pay gap still exists.

If indeed women are taking jobs away from men in OB/GYN they are only taking away the lower paying ones freeing men up to stay in the higher paying positions.

It is still harder for women in medicine. Period.

When there hasn’t been a male President of ACOG for 10 years and all OB/GYN textbooks are written by women and no one asks me if I am a nurse or forgets to call me doctor when they introduce me at a professional function and when women out earn men in OB/GYN and have 80% of the leadership positions and when opinion pieces about the dearth of women in surgery and the excess of women in pediatrics fill our newspapers and when men are asked about their procreation plans at interviews I will be concerned that OB/GYN has developed a gender diversty problem. However, as the women I have worked with in medicine tend to be concerned with all stake holdeers equally and support parity because they have been on the receiving end of inequality I doubt we will ever see that kind of bleak, all female future.

It is true that most residents in OB/GYN are women, but a man who wants to go into OB/GYN will never, ever face the systemic oppression and bias and lack of role models that women have faced and still face today. Any man in OB/GYN on graduating residency will likely end up with a higher paying job than the women he trained with and history tells us he won’t seem to mind. After all, if men in OB/GYN minded so much about the gender pay gap we wouldn’t have one because they have always been, and are still, the ones in charge.

*** This post has been updated to reflect there have been 5 women Presidents at ACOG in 65 years, not 4 as originally stated***

Paul Elam of A Voice for Men: Now officially a hatemonger

By David Futrelle

A big round of applause for two websites that have featured here on We Hunted the Mammoth from the beginning: A Voice for Men and Return of Kings have both been officially recognized by the Southern Poverty Law Center as hate groups.

The hate-monitoring group announced the news in its latest “Year in Hate” report yesterday. “[F]or the first time,” the report declared,

the SPLC added two male supremacy groups to the hate group list: A Voice for Men, based in Houston, and Return of Kings, based in Washington, D.C. The vilification of women by these groups makes them no different than other groups that demean entire populations, such as the LGBT community, Muslims or Jews, based on their inherent characteristics.

Both groups have more than earned this long-overdue designation. If you need to be reminded just how, take a stroll through the archives here for literally hundreds of examples of hateful rhetoric and actions by both AVFM and RoK, and/or their respective founders, Paul Elam and Roosh V.

You may also notice, in your stroll through the archives, that both AVFM and (especially) RoK have embraced some of the most noxious views of the racist alt-right directly. Indeed, one of the most notorious participants in the racist Charlottesville march last year — a man jailed for his assault on a counterprotester — was a former contributor to AVFM.

Elam’s response so far to his recognition as a hatemonger by the SPLC has actually been somewhat tame, at least by his standards.

Being called a hate group by the SPLC is like being called fat by Rosie O'Donnellhttps://t.co/UZRhPl40jm

— Paul Elam (@anearformen) February 21, 2018

Hey @splcenter Just a note of thanks for adding me to your Hate Watch list. If I have raised the ire of you money grubbing, POS shyster con artists, then I must be doing something right. #WhatTookYouSoLong

— Paul Elam (@anearformen) February 21, 2018

He also retweeted this lovely sentiment from someone whose Twitter handle is a not-very-subtle reference to the c-word.

Hahahaha 'Male Supremacy Groups' FFS.

Women are being forced, pushed, launched, catapulted & carried forward on the corpses of men & boys & yet MALE FUCKING SUPREMACY GROUPS? REALLY.

Hey SPLC … Fuck off with your twisted Nazi hate propaganda.

YOU ARE FIRST AGAINST THE WALL. https://t.co/FGFFAWNdkc

— Krunt Frucker (@KruntFrucker) February 21, 2018

This dude was even more pissed:

They fucking added a voice for men to a fucking hate list jesus fucking christ, feminism is a cancer and all feminists should be shot @frozenbinarydev @notCursedE @PriestessOfKek https://t.co/yBpfBcmzRZ

— HasBaal (@has_baal) February 21, 2018

Roosh’s response to his inclusion on the list was a bit, shall we say, ironic as well:

The Jews are coming after me again https://t.co/ql6iUFwm0B

— Roosh (@rooshv) February 21, 2018

Thanks for proving the SPLC’s point, guys!

The SPLC report also notes a number of other discomfiting facts, starting with this one:

The SPLC’s Year in Hate and Extremism report identifies 954 hate groups – an increase of 4 percent from 2016.

Some of this increase, the report says, was due to a resurgence of fringe black nationalist groups — which the SPLC is quick to distinguish from “activist groups such as Black Lives Matter and others that work for civil rights and to eliminate systemic racism.”

But the real danger comes from the racist right.

[B]lack nationalist groups lagged far behind the more than 600 hate groups that adhere to some form of white supremacist ideology – and they have virtually no supporters or influence in mainstream politics, much less in the White House.

Within the white supremacist movement, neo-Nazi groups saw the greatest growth – from 99 groups to 121. Anti-Muslim groups rose for a third straight year. They increased from 101 chapters to 114 in 2017 – growth that comes after the groups tripled in number a year earlier.

Ku Klux Klan groups, meanwhile, fell from 130 groups to 72. The decline is a clear indication that the new generation of white supremacists is rejecting the Klan’s hoods and robes for the hipper image of the more loosely organized alt-right movement.

The overall number of hate groups likely understates the real level of hate in America, because a growing number of extremists, particularly those who identify with the alt-right, operate mainly online and may not be formally affiliated with a hate group.

These groups not only spew hatred; they have helped to spur a frightening rise in racist violence — and murder.

A separate SPLC investigation, released earlier this month, found that 43 people were killed and 67 wounded by young men associated with the alt-right over the past four years. Seventeen of the deaths came in 2017.

So AVFM and RoK are in some pretty shitty company here.

What did Donald Trump do today?

Crooked Hillary said that I want guns brought into the school classroom. Wrong!— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 22, 2016

Why should I care about this?

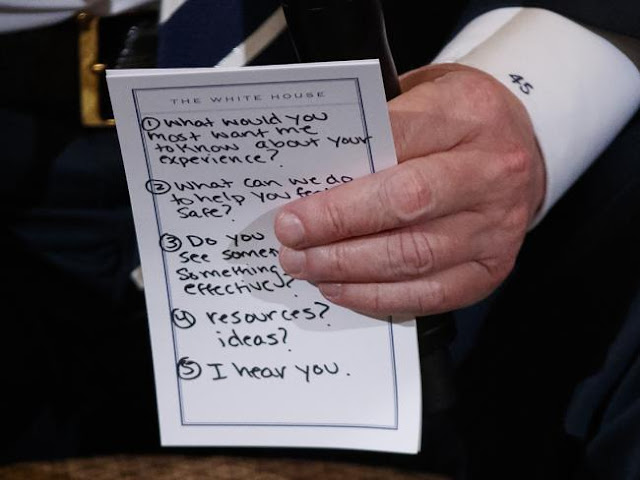

- It's bad if the president needs to be reminded of how to act like he's listening.

- Presidents should not lie about their policies.

- Presidents should not use tragedies to advance political ends.

- Inability to show or feel empathy is not a sign of good mental health.